Waste Recycling Emerging as a Strategic Pillar for Critical Minerals

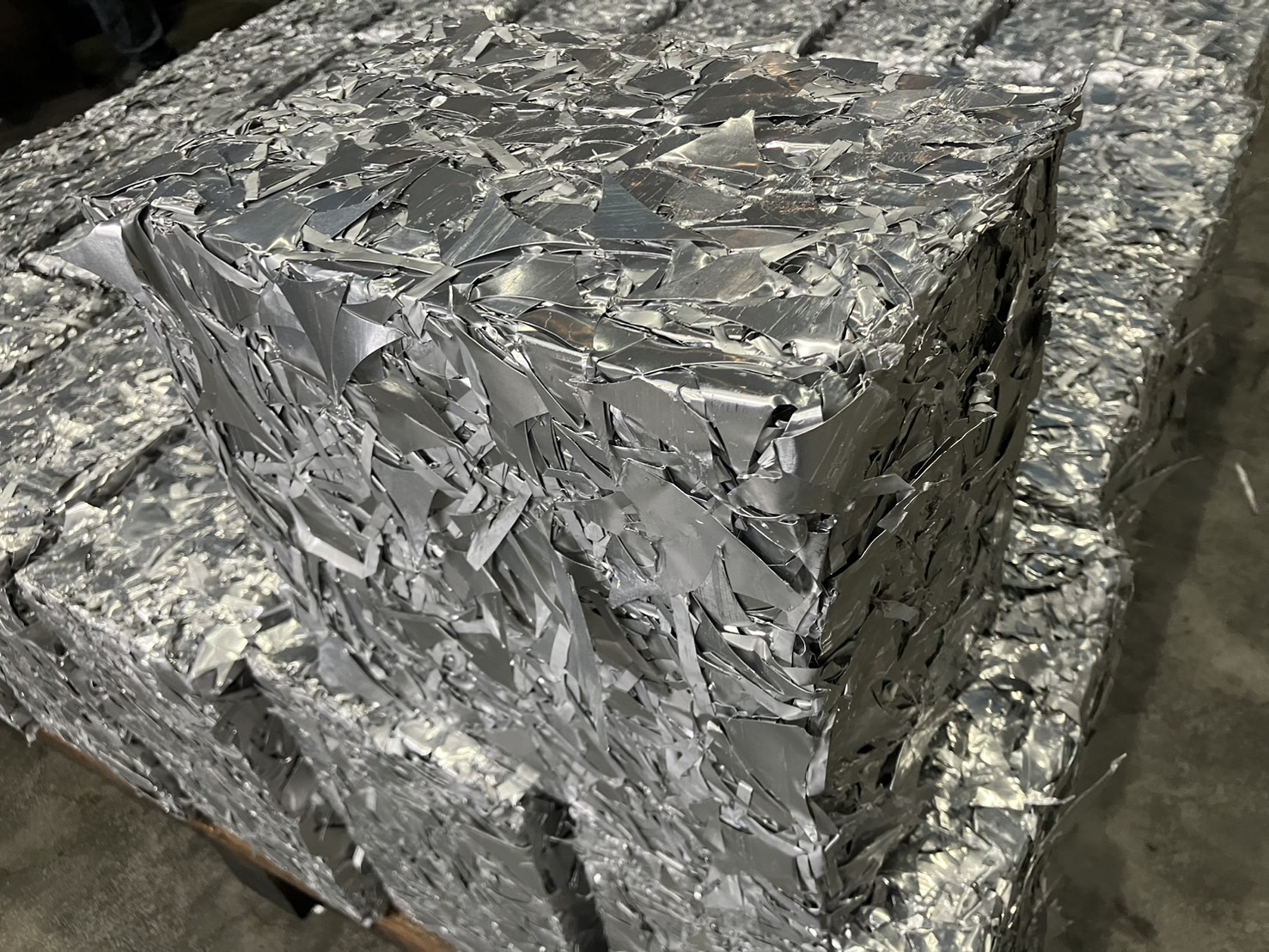

1. The Rising Strategic Value of Aluminum Scrap

As global demand for electric vehicles, renewable energy systems, and defense-related materials continues to rise, the minerals required to support these industries have become the focal point of international competition. Recent industry analyses reveal that a new wave of supply chain dynamics is quietly shifting from traditional mining sites toward recycling centers—particularly those handling aluminum scrap, once regarded as a low-value material.

A Reuters analysis published in late 2025 described aluminum scrap as “the new battlefield in the critical minerals race,” noting that Europe exports large volumes of aluminum scrap each year while simultaneously seeking to rely on recycling to meet its decarbonization and industrial resilience goals. This contradiction has prompted the EU to consider tighter monitoring and potential restrictions on scrap exports.

In this context, urban mining—recovering metals from end-of-life products and municipal waste—has evolved from an environmental concept into a practical strategy adopted by major economies such as the U.S. and the EU. Aluminum scrap has consequently shifted from a peripheral recycling material to a strategic resource within the critical minerals supply chain.

2. Energy Efficiency Driving the Rise of the Recycling Economy

The increasing attention on aluminum recycling is rooted in its exceptional energy efficiency and circular potential. According to the International Aluminium Institute, producing secondary (recycled) aluminum requires only about 5% of the energy needed to produce primary aluminum, resulting in approximately 95% energy savings. Studies also indicate comparable reductions in greenhouse gas emissions.

In an era shaped by carbon pricing, carbon tariffs, and national net-zero commitments, such efficiency advantages translate directly into lower operating costs and stronger trade competitiveness. For governments, strengthening recycling and secondary metal production often provides a more cost-effective and publicly acceptable alternative to opening new mines or building energy-intensive smelters. For corporations, increasing recycled aluminum usage reduces carbon footprints and supports growing requirements for green procurement and sustainable product standards.

3. The U.S. Challenge: Declining Smelting Capacity and a Greater Reliance on Recycling

The United States illustrates the broader challenges faced by advanced economies. While aluminum is officially recognized as a critical mineral by U.S. authorities due to its importance in EVs, aerospace, defense, and infrastructure, America’s primary aluminum smelting capacity has declined significantly over the past several decades.

During the latter half of the 20th century, the U.S. was one of the world’s largest aluminum producers. By the 2020s, however, its share of global primary aluminum production had fallen to below 2%, with production costs affected by high electricity prices, stringent environmental standards, and rising competition from emerging producers.

At the same time, the U.S. generates large volumes of aluminum scrap and is one of the world’s key exporters. Industry associations have noted that a substantial portion of this scrap is shipped overseas—including to countries rapidly expanding their secondary aluminum capacity. In 2025, the Aluminum Association openly urged the U.S. government to classify used beverage cans as a strategic resource, advocating for export restrictions to prioritize domestic use by automotive, aerospace, and defense industries.

Under these circumstances, recycling and secondary aluminum production are no longer supplementary activities but essential tools for reducing import dependence and enhancing supply chain resilience.

4. Global Competition: The Pivotal Roles of China and Southeast Asia

China and Southeast Asia have become increasingly influential in the global aluminum and secondary metals supply landscape. China remains one of the world’s largest primary aluminum producers and has invested heavily in expanding its recycling and secondary aluminum capacity. Industry reports indicate that China plans to significantly increase its recycled aluminum output in the coming years, aiming to reduce reliance on high-carbon primary smelting.

Southeast Asia, meanwhile, has emerged as a major processing and transshipment hub. Countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam receive aluminum scrap from Europe, the U.S., and East Asia, while also developing domestic recycling and secondary aluminum industries. Competitive electricity prices, labor availability, and geographic proximity have made the region a key node in global aluminum scrap flows.

For the U.S. and Europe—both seeking to diversify supply chains away from single-source dependencies—investing in refining and recycling capacity in Southeast Asia has become an attractive strategic option. Newly established critical minerals partnerships reflect this shift toward securing more stable secondary resource channels.

5. Clear Advantages, but Global Recycling Rates Still Have Room to Improve

From a materials science perspective, metals such as aluminum and copper have exceptionally high circular potential. When properly collected and processed, they can be recycled repeatedly without significant loss of performance. However, reports by the International Energy Agency and the United Nations show that the share of secondary supply for many critical minerals has remained stagnant or has even declined in recent years, suggesting that existing recycling systems and economic incentives remain insufficient to keep pace with rising demand.

Aluminum is a relative bright spot. International studies indicate that mature markets already operate well-developed aluminum recycling systems, with secondary aluminum slowly increasing its share of total supply—especially in packaging and construction sectors. Yet even this falls short of aluminum’s theoretical recycling potential. Strengthening collection systems, refining price mechanisms, and enhancing cross-border cooperation will be key to unlocking aluminum’s full role as a circular metal.

6. Policy Shifts: Rebalancing from Mining to Recycling

Amid green transition pressures and geopolitical risks, major economies are reframing their critical mineral strategies—from focusing primarily on mining to building balanced systems that integrate both primary extraction and secondary recovery. The IEA’s Critical Minerals Recycling report emphasizes that while recycling cannot fully replace new mining, it can serve as a significant supplementary source, reducing demand for new extraction and mitigating the environmental and social impacts associated with mining.

In Europe, concerns over aluminum scrap outflows have led industry associations in the aluminum and steel sectors to jointly call for export controls or additional duties, arguing that uncontrolled exports undermine Europe’s decarbonization and industrial goals. The European Commission has since launched monitoring mechanisms for scrap exports and is exploring additional measures to preserve critical recyclable resources within the region.

In the United States, beyond tariff policies, industry stakeholders have also proposed new frameworks. The Aluminum Association’s 2025 white paper—positioning used beverage cans as “strategic assets”—advocates for export controls, refined customs classifications, and stronger investment in domestic recycling technologies to enhance the processing of various grades of scrap.

Conclusion:

Aluminum Scrap as a Critical Piece of the New Supply Chain Strategy

The growing importance of aluminum scrap signals a fundamental shift in global critical mineral strategy. Competition is no longer confined to mines and smelting capacity; instead, it increasingly centers on access to recyclable resources and the ability to establish efficient, low-carbon secondary production chains.

For nations, this shift touches on energy transition, industrial competitiveness, and national security. For companies, it directly affects cost structures, carbon performance, and future market access. In this evolving landscape, aluminum scrap is no longer a by-product of consumption but a revalued strategic asset.

Those who invest early in recycling, secondary production, and circular supply chains will be better positioned to lead in the next phase of the green industrial transition. In this sense, “waste” is no longer waste at all—it is an essential component of the modern critical minerals strategy.